| Long before the coronavirus pandemic, stretching back to even before the Great Recession, the notion of a driver hiring crunch was in the air.

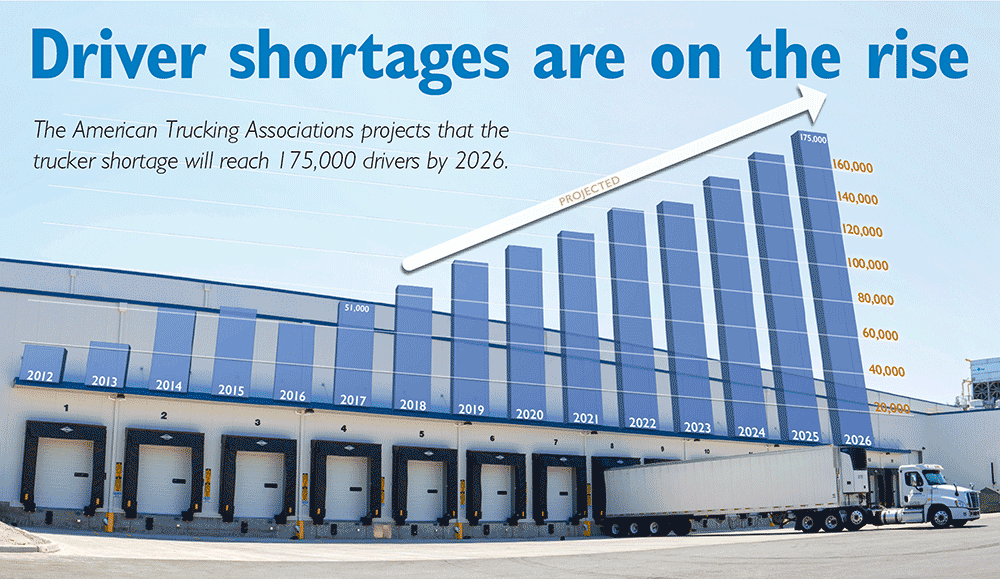

Back in 2005, the American Trucking Associations (ATA) documented a shortage of roughly 20,000 drivers. The numbers ebbed slightly during the Great Recession as volumes plummeted, but by 2017 the shortage had grown to about 50,000 drivers. And then this recent news: On Oct. 26, The ATA reported that the truck driver shortage will climb to a record high of just over 80,000 drivers. That number may soar to 160,000 in fewer than 10 years. Today, the labor shortage in transportation extends not only to drivers but also to maintenance technicians, loading dock workers, and package sorters. It’s part of an even broader post-pandemic trend encompassing other industries, particularly in service and hospitality. Double whammy: Fleets are now having to compete with other job types that are pulling workers out of the driver pool. “There is an adjustment happening to the labor force, and those other occupations are not immune to what’s been happening in transportation for some time,” says Mark Murrell, president of CarriersEdge, a provider of online driver training for trucking and other fleets. There is a growing sense that this broader market disruption isn’t temporary and is the beginning of a longer-term change. If true, “That’s going to require a new definition of what the work is,” Murrell says. “(And) we’re going to have to find ways to make the job more attractive.” For fleets, the Code Red alarm has seemingly been blinking for years, and yet the problem only intensifies. While it’s easy to engage in unproductive handwringing, this misses an opportunity to solve it, Murrell contends. Murrell recommends viewing the problem through the lens of driver retention — which is, ironically, good news for fleets. “You’re not going to solve the industry’s labor crunch,” Murrell says. “But if you can improve your retention by 10% or 20%, that’s a lot fewer positions you need to fill.” What can fleets do to improve driver retention? Murrell has a few recommendations. And some require a fresh perspective on commonly held notions.

Understand when driver turnover occurs.During the pandemic, CarriersEdge analyzed data across multiple fleets on when driver turnover occurs in the employment cycle. “Conventional wisdom is that most turnover happens in the first 90 days,” Murrell says. “We found that wasn’t the case at all.” Murrell acknowledges that an appreciable number of drivers do quit within the first 90 days, but it’s not the largest segment. “What was surprising to us was that the greatest turnover happens after a year’s tenure,” he says. “It may very well be that people are sticking around for a while and they start to stagnate, they don’t see any future, or they get bored with the work.” Knowing when turnover occurs informs how and where you act: Survey your drivers.Ask your drivers what they want. Find out the top three things that they like about their jobs, and the top three they’d like to see changed. “Highlight the good things as part of your brand building and when you’re hiring,” Murrell says. “And the things that need to change, start with the low-hanging fruit.” It’s important to survey the new hires in the first month or two. “But don’t forget about the people that have been around for five or 10 years and keep them involved as well,” he says, which will provide insights into how and if they’re stagnating. Your seasoned drivers factor into the next tactic: Create a driver advisory board.Gather your more tenured drivers to create a driver advisory board. This group will be your sounding board for implementing changes, finding ways to help build the business, and serve as a collective window into drivers’ wants and needs. Involving your veterans gives them more responsibility and has retention value itself, Murrell says. It’s hard to get a group together these days, but the new environment of virtual video conferencing makes conducting meetings a lot easier. Expand professional development.For professional drivers, defining a career path is not as straightforward as other jobs that involve driving. For instance, the sales rep road warriors have a path to sales executive positions and service technicians can assume supervisory roles. Yet professional drivers will likely have the same job five or 10 years down the road. “The advisory board can really help here by working with management to figure out how to keep workers engaged and give them something fulfilling once they’ve figured out how to do the job.” Murrell says. Knowing when driver turnover occurs will also benefit this initiative. “Most fleets concentrate their professional development efforts within the first year,” he says. “What training do drivers get who’ve been around for three years or five years? The answer is not much.” The development doesn’t have to involve more pay or even a title change — what’s most important is to figure out new challenges and responsibilities that demonstrate a growth path. In addition to the advisory board, veteran drivers are candidates to mentor: “Tap their experience and share it with new drivers,” Murrell suggests. Let your drivers congregate online.The nature of a driving job means less of a connection to a centralized team that congregates daily. “Companies have to work harder on making drivers feel like they’re part of something,” Murrell says. Giving drivers a place to connect online is one solution. “Drivers love Facebook,” he says. “It’s a great way for them to connect with their peers and management.” Murrell has also noticed how drivers will self-organize into Facebook groups and pages by region or by the specific type of work they’re doing. In addition to chat groups, some companies conduct driver meetings as Facebook Live events. “They can participate from anywhere and they can comment,” he says. “It can be lighthearted, but they can feel like they’re part of something and they don’t have to show up at the warehouse on a Saturday morning.” Reassess gamification.Rewards programs based on driver metrics, or gamification, were all the rage 10 years ago in the corporate world, though adoption has wanted. Types of jobs with younger workers, such as gas stations and fast food, still use gamification. But the 20-year driver veteran doesn’t relate in that way, Murrell says. “It’s fun for a bit, but it ends up being a distraction, and some might get insulted by it.” “We hear from drivers that they don’t want to be treated like a child,” he continues. “We’ve found they’d rather be treated like professionals and to build around that assumption, rather than ‘Let’s make it a game.’ This is a job, not Friday night with friends.” Murrell warns that rewards programs can’t be used in lieu of compensation, such as accruing points for finishing training or showing up on time. A limited metric-based award system can be effective, however. Going back to driver communication — survey your drivers for honest answers on what’s effective for them. Recognize your drivers.This is an obvious point, but one that needs consistent reinforcement from management because it ends up being overlooked, Murrell says. This works particularly well with veteran drivers because it allows them to be recognized as leaders amongst their peers. Like professional development, this recognition doesn’t have to come with more pay or a title change. But consider branding work gear or even the side of a truck with a senior driver’s responsibility. “That’s effectively a career path that doesn’t exist in more formal ways,” he says.

Originally posted on Automotive Fleet |